Thanksgiving, for much of its existence, has been used as a community event to bolster morale and solidarity among people, particularly to express major gratitude for survival following periods of duress. Today, it is more commonly used as a kind of psycho-social evaluation to observe how well-equipped we are to handle close quarters with family members.

Colonial Thanksgivings

Most people today are aware of Thanksgiving's colonial origins to some degree. The story goes that in November 1621, Governor William Bradford of Massachusetts Plymouth Bay Colony organized a celebratory feast for the season's successful corn harvest, with the Wampanoag Native Americans. The next Thanksgiving was 2 years later in 1623, at the end of a long drought that had threatened the harvest and prompted the governor to call for a religious fast. Although popular marketing of the holiday boasts achievements of continued cooperation in good faith, the ongoing reality of the American Indigenous plight will not go unnoted.

For European-American settlers in New England colonies, days of fasting and thanksgiving were practiced sporadically and declared locally to give thanks annually or occasionally for specific events such as the end of a drought, victory in battle, or after a harvest.

Thanksgiving As a National Holiday

Before we enjoyed the predictability of a late November holiday, Thanksgiving happened whenever the President put it on the calendar. It was the President’s duty to decide when a nationwide day of gratitude would take place. The first president of the United States, George Washington, decided that the holiday would be held on Thursday, November 26th in 1789, celebrating the conclusion of much revolutionary unrest. The second president, John Adams, declared two Thanksgivings: in May of 1798 and April of 1799. The third president, however, decided not to have Thanksgiving at all. During Thomas Jefferson's term, it was debated that the holiday was antithetical to American principle, because it made room for state-sponsored religious practice. Critics chided Jefferson’s alleged atheism as hubris, but he firmly upheld “a wall of separation between Church and State.”

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship…I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act…which declared that…legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation…I shall see…the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore man to all his natural rights….”

— Thomas Jefferson in an 1802 response letter to the Danbury Baptists who lobbied him to fortify the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious liberty.

After Jefferson's presidency, fourth president James Madison revived the tradition with vigor, proclaiming four Thanksgivings during his term. From 1812 to 1815, Thanksgiving Day took place during the months of August, September, January, and April. Thanksgiving Day continued to be proclaimed intermittently in following presidencies, with no executive push towards temporal fixedness or consistency -- until Abraham Lincoln's wartime presidency.

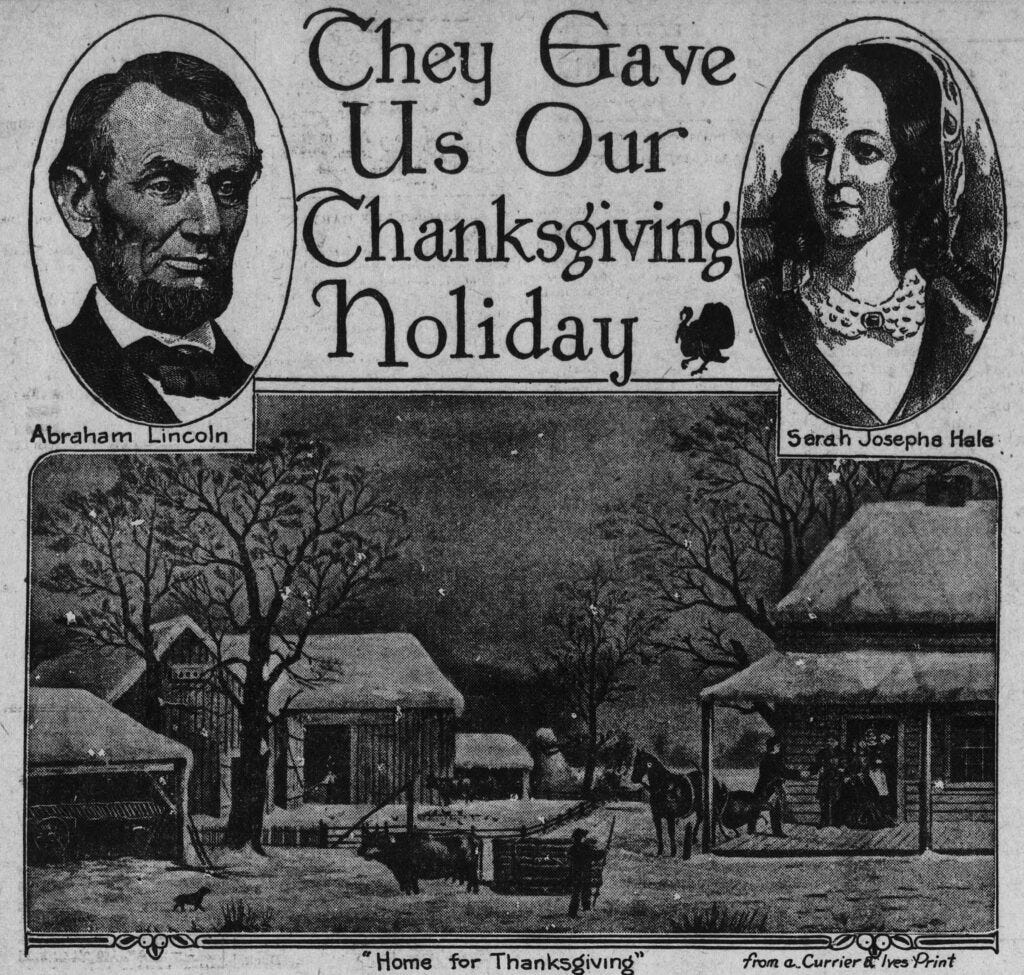

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate governments had called for separate Thanksgiving Days, following their own victories and the losses of their opposition. The opportunity to create national unity through Thanksgiving was brought to public attention by a woman named Sarah Josepha Hale (famously credited for the timeless banger: Mary Had A Little Lamb). She was the editor of the most widely circulated magazine leading up to the Civil War. Over the course of decades, Hale lobbied Congress and five different presidents, including Lincoln, to establish Thanksgiving as a day of gratitude during the New England autumn harvest. In that region, the tradition of Thanksgiving was well established in many households. Much of Hale’s activism involved great respect for positions of domesticity and creating more public value for women's traditional roles. She supported employment and higher education for the contemporary American woman. Today, Hale can be recognized alongside Lincoln for the establishment of the national holiday. In her letter to Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, she urged for Thanksgiving to become “permanently, an American custom and institution.” Soon after her correspondence, her vision was realized. A proclamation was issued, establishing the holiday to be every last Thursday of November. And so it was, until 1939.

In 1939, there were five Thursdays in November, so the last Thursday of November landed on the 30th, leaving only 24 shopping days before Christmas. FDR, influenced by the Great Depression, was urged by US retailers to move Thanksgiving back a week to increase the number of shopping days, and boost sales. FDR obliged, changing Thanksgiving to the second to last November of the month. No significant increase in sales was observed, but much confusion was experienced due to this seemingly arbitrary federal decision. Calendars were thrown off, schedules were shuffled, and American people were upset.

Eventually in 1941, Congress passed a law declaring that Thanksgiving would occur every year on the fourth Thursday of November, and the federal holiday has been well-behaved ever since.

Thanksgiving, 2023: A Long Island Narrative

This year, there are five Thursdays in November once again, and I must say that I am thankful for the extra week of Christmas consumerism that these well-placed dates have provided me, as I fancy myself a professional procrastinator. Earlier this week, I productively procrastinated by taking a walk through the southernmost neighborhood of Shirley, a town footed by the ocean and flanked by the bay. At the final bend in that particular road, only a pedestrian would have been able to detect the gap in the streetside cattails, revealing a narrow path through the tall grass. Pedestrians we were, so into the brush we carried on, one foot over the other, minding the marshy bits, until the dirt trail opened revealing a long stretch of street-width concrete. An abandoned street, so it seemed, with no trace of surrounding man-made structure. Just the street. Roots of plants pushed up through the cracks, lining the faults of the forgotten road with grass, wildflowers and even small trees that were beginning to survive where concrete had once been poured over the earth with the intention of permanence. We silently weaved through the length of the overgrown road, unsure of our destination. Just as silent were the deer embedded in the landscape, quietly flitting away as we neared. With time, the low brush dwindled further into a sandy clearing where the blue sky arched high, framing the great dimension of two rusty orange construction vehicles, and a tall pile of erosion control material. From my brief stint in local landscape construction, I recognized this to be a wetland protection project. Massive logs of coconut fiber called coir were to be strategically placed along the shoreline to hold natural erosion at bay (no pun intended). A little walk onwards, and we ultimately reached the Smith Point Marina Park, named for early New York settler William "Tangier" Smith. Smith was a native of England, who also served as mayor of Tangier, Morocco. Smith purchased tens of thousands of acres of ocean-front property from the Poospatuck Unkechaug people in what is now Shirley-Mastic, Long Island.

Years ago, when my vices were many and my inhibitions few, my footfalls loud and my voice hoarse, the Smith Point area of Shirley-Mastic was only of importance to me when I was running dangerously low on cigarettes. When that happened, I would type "Poospatuck" into Google Maps, the search results returning the address for a smoke shop tucked into the Poospatuck native reservation: 55 remaining acres (less than a tenth of one square mile) of home to less than 500 people who have yet to be federally recognized by the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. I would leave the Poospatuck reservation as brazenly as I came, 100 cigarettes richer for $10. It was a steal.

I digress.

It is with great enthusiasm, and some tangential digression of undisputable necessity, that I am able to lay out just some of the fascinating and extensive documented history of this American practice known as Thanksgiving Day. From Puritan harvests, to Civil War conquests and bureaucratic scheduling blunders, we can observe the interplay of environmental and sociopolitical conditions shaping our cultural rituals. With that, as we gather this Thanksgiving, testing our tolerance for those who sit around our own tables, let us not forget the ground on which we stand and the earth that turned to feed us. Let us choose wisely what guides our hand in times of hunger, when we do not know what we do not know. Where blood flows, grain grows.

“Even a wounded world is feeding us. Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy. I choose joy over despair. Not because I have my head in the sand, but because joy is what the earth gives me daily and I must return the gift.”

—Robin Wall Kimmerer, Potawatomi Botanist

This article is written with hope to promote Decolonizing Thanksgiving, an event centered around mindful conversation and dialogue, hosted by Teatro Yerba Bruja, an experimental art collective, in Bay Shore, Long Island, New York. For more information, please visit https://www.teatroyerbabruja.org/mission .