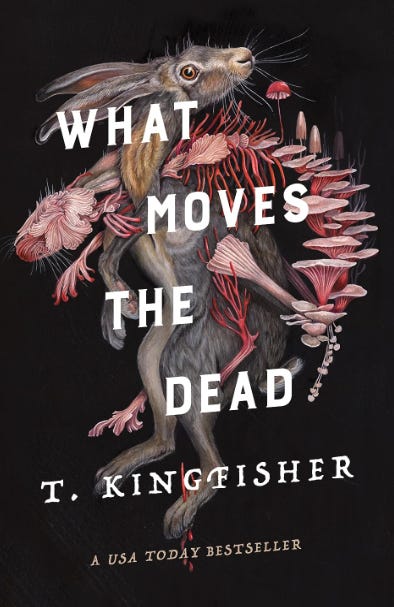

The inevitability of my consumerism led me here. My historic inability to engage in longform reading frightens me in a horrific way, however this easily digested macabre seemed to scare some wit back into me. Cover to cover thinner than my pinky and less costly than a Starbucks cup of coffee—no threat detected. To my great pleasure, the first few pages of this book installed its parallel structure to Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. A familiar plot is difficult to derail, and who doesn’t love romanticized death and decay with millennial pink oyster mushrooms stamped on the cover? If you are like me, and you struggle to dedicate hours to literary consumption, I’ve condensed my understanding of this text in what should take about 7 minutes to read. Straight to the point, of course.

As an aside, I must note the incidence of eyes, and eyeballs, and retinas, and corneas. How fascinating, that we evolved these external appendages, extending directly from our brains, and out through our skeletons, as telescopic mechanisms of perception. I like to imagine the organs’ evolution as pioneering, curiously decentralizing from brain mass, exploring further through and through the skull, with artery telephone lines connecting them back to home base.

Goats’ pupils are rectangular to allow for a wider field of vision. Do they see in IMAX?

Officer Easton’s field of vision presents a drab and dreary scene, moist and sludgy, like a sweaty oil painting. In accepting the invitation of an old-service mate, our protagonist trudges towards the House of Usher, through the miserable tarn alongside Hob the healthy steed, meeting an earthy mycologist on their way through the wood. The scientist’s gaze is fixed with scholarship to the ground, and she does not envy our protagonist’s destination. The viscous and foggy estate mirrors that of Poe’s original House of Usher, and its inhabitants are just as unstable and murky. Roderick and Madeline are the last facilitators of the property, passing it into —what or where exactly? We can’t be sure, but the surviving Ushers seem determined to deliver what is left. And what is left is a house too big to be heated properly, too labyrinthine to be inviting, and too depressing to stay too long without killing yourself, at least that was the case for the maidservant that expired with a thud out of the 5th floor window a week before Easton’s arrival. All ailments of the estate prove proximity to death, and the unnaturally luminous lake at its center has benignly nefarious character.

Artist Dasha Plesen combines molds, bacteria, spores, and other objects in petri dishes to create these colorful abstract photographs.

Officer Easton is a solemn and likeable character, a traveling ex-soldier, whose gender is of the utmost unimportance, except when it comes to those dreaded pronouns. Easton’s native language is so filled with pronouns it makes English seem simple. Ka, va , ta…pronouns for this type of person, that type of person, etc. etc. This foreign complication reminds me of how in Bahasa Indonesia, the language of Indonesia, there are at least 4 different ways to say “I”, depending on who you’re talking to at the time. Here, language reflects the cultural value of hierarchy. You wouldn’t be caught dead referring to yourself as “aku” to a respected elder. “Saya”, “awa”, or even referring to yourself by name in the third person might be warranted. Imagine having to shift the way you referred to yourself solely based off the difference in station that existed between you and your addressee. An American could never. Ursula Vernon is the woman behind the pen behind title author T. Kingfisher, and incidentally, Ursula Vernon is an American. I learned of her citizenship via the internet, but I should have known it based on her forward jabs at the American stereotype, as is seen in the text.

‘“How do you do?” Denton said.

Ah. American. That explained the clothes and the way he stood with his legs wide and his elbows out, as if he had a great deal more space than was actually available.’

—Our protagonist is introduced to a doctor from America.

Easton’s stay at the House of Usher is as dismal as one could expect, considering this particular visit was prompted by a dreadful letter from Roderick Usher, delivering fear that Madeline, the host’s dear sister, and genuine friend of Easton, was dying. It bears mentioning that Roderick himself withers away casually. Once a soldier alongside Easton, the eldest Usher is now shrouded in an ill frailty challenging that of his sister. However, a healthy dose of reminiscing is the mind’s Tylenol. Roderick recounts active duty, Madeline dreams of lemon ice and Paris, and Easton reflects on the infallible loyalty of his batman Angus, who continues to serve with great sincerity. Wouldn’t it be nice to inherit the most trusted hand and advisor of your father, to be at your side whether in peace or at war? I suppose that would really depend on the type of relationship you have with your father. Easton seems to have lucked out on that end— a well-rounded protagonist, a sworn sword, a real rationalist.

Together, our cast of characters assemble a collection of occurring oddities that, for the sake of their collective sanity, mental and physical wellbeing, must be connected.

The lake is alive, the vacant-eyed rabbits have forgotten how to run, and Madeline is forgetting how to breathe? How to remain conscious? How to refrain from drowning herself in the petri dish lake? Easton thinks maybe they all need more protein and arranges steak dinner with the boys. No luck, Madeline seems to only get worse, both mental and physical constitution failing, and a closer look at her pallor discloses that she’s actually got these wispy white fibers flowing like cilia out from under her paper skin.

“Fungal spores infect house flies by hitchhiking on a fly's exoskeleton, germinating and then breaking through the fly's tough outer cuticle. "The fungus then starts growing inside the hemocoel — the bloodstream — of the fly," absorbing nutrients from the fly's body as it grows, Hansen said. The infected fly dies about five to eight days later, and spores emerge from the dead insect approximately two hours after death.”

—https://www.livescience.com/fungus-flies-mate-dead-infected-females

You guessed it! It’s like the plot of The Last of Us. Parasitic fungi zombie syndrome, if you will. The aforementioned woodswoman mycologist assists our plot in arriving at a conclusion: the fungi inhabiting the lake was infecting the House of Usher, slowly sapping life from living bodies, and subsequently using newly acquired advanced form to ensure their continued repopulation and growth. They were even beginning to learn basic language before Easton and remaining company were compelled to extinguish their existence as efficiently as possible (with fire and brimstone of course).

I find it rather limiting to simplify the plotline by referring to the mysterious organism as zombie fungi. The zombies are not quite zombies. They are not quite death reanimated. They are the artistic biological ventriloquy of the will to live. They are free will, they are intention unimpeded, they are qadar. They are learning how to be more— what the Jesuits might consider a pursuit of magis. Is the pursuit of life an inalienable right of the living? If so, then the zombie fungi terrorizing the House of Usher were simply an unfortunate underdog. If not, then I am curious what distinguishes human survival from parasitic abuse.

Curiously and closely, Greed was recently posited to me as a human virtue, with the defense that Greed serves as a necessary motive for improvement with respect to continued survival. As a stark and self-proclaimed anti-capitalist by intention of hyperbolic impact, I struggle to find truth in this proposed virtue of Greed. To the credit of the counterargument, it can ostensibly be asserted that Greed and material desire have proven to be a successful driver for advancement, with material gain dangling like a carrot on a stick for innovations in technology, medicine, as well as personal and genealogical wealth, to name a few. Protonsil, an experimental antibacterial drug, saved FDR Jr. from a deadly strep strain he contracted at a party, because Bayer had the available funds by contract to enlist great minds in the drug’s development. No money, no motive, no Mr. President Jr. Perhaps this is a topic to revisit outside the confines of a book review, but I will for the time being acquiesce with qualification as follows:

If Greed can drive growth, then Sharing propels progress.

But who’s to say what moves the dead?

Thank you for reading! This is part one of twenty-four, in step with my local library’s challenge to read 24 books in 2024. Next up is The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World, by Michael Pollan, which is so far proving itself to be masterful storytelling of the natural evolution and oral history of the apple, tulip, marijuana, and the potato.